Academic Research

“Life has no blessing like a wise friend.” - Euripides

I study how interpersonal relationships enable people to cope

effectively with challenges and achieve important goals.

My work is driven by two main questions: How can people help each other manage difficulties? And, how do partners coordinate as a unit?

In pursuit of these questions, I have constructed new theoretical perspectives to illuminate how relationships contribute to well-being. Furthermore, I have leveraged diverse methodologies, including experiments, psychophysiology, and daily experience techniques to reveal key implications of relationship processes across domains and at multiple levels of analysis. Finally, I have developed and implemented state of the art statistical methods to provide the most rigorous and theory-driven tests of my hypotheses. Overall, my research program bridges work on self-regulation, emotion, and lifespan development to advance understanding of how people organize within complex social systems.

How can people help each other manage difficulties?

Social support, which refers to practical and emotional assistance from others, is arguably the most vital function of social relationships. Although it is often assumed that social support is universally helpful, empirical evidence has been mixed: Support can sometimes alleviate people’s distress but can also undermine their feelings of competence. I have developed a theoretical perspective to reconcile these mixed findings: I propose that social support is most effective when it addresses support recipients’ motivational needs. I have found robust evidence for this proposition across several studies examining support among strangers and existing relationship partners using a combination of experimental, dyadic, and psychophysiological approaches (Zee, Cavallo, Flores, Bolger, & Higgins, 2018; Zee, Bolger, & Higgins, 2020; Zee & Kumashiro, 2019; Cavallo, Zee, & Higgins, 2016; Cavallo, Zee, & Higgins, in preparation).

In one project, I found that recipients who received support given in a manner (visible vs. invisible; Zee & Bolger, 2019, Current Directions in Psychological Science) that matched their motivational orientation felt less distressed, experienced higher self-efficacy, and showed tempered cardiovascular reactivity during a laboratory stressor (Zee et al., 2018, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology).

In subsequent research, I created a theoretical construct to reveal which motivational needs matter most in support contexts and how addressing them uniquely fosters effective goal pursuit (Zee, Bolger & Higgins, 2020, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology). My construct, Regulatory Effectiveness of Support (RES), posits social support that addresses recipients’ motivation to understand and manage their situation enables them to feel effective and succeed on important goals. I found that self-reported and observer-rated RES predicted benefits such as better mood and tempered cardiovascular stress. I also found that RES had downstream implications for performance: People who received support higher on RES felt more motivated to perform well on a stressful speech, and performed better, as rated by independent observers.

Overall, my research in this area offers an explanation for the mixed effects of support found in prior work and demonstrates the power of addressing motivation to enhance support’s effectiveness.

How do relationship partners coordinate as a unit?

Coordinating with others is an essential part of everyday life. In a second line of research, I study how people coordinate as a unit. My work in this area has largely focused on coregulation in dyadic interactions. Coregulation is a process in which interaction partners experience dynamic coupling of their emotional and physiological states, which stabilizes their responses in the face of difficulties. For instance, a person who has received upsetting feedback might seek out a close friend, and, by drawing on their friend’s calmer state, recover more efficiently.

I have investigated when and why dyads coregulate (Zee & Bolger, 2020, Multivariate Behavioral Research; Zee & Bolger, under review. Preprint). I showed that physiological coregulation emerges during support discussions, in which partners make explicit attempts to bring each other back to a calmer state. Through synchronizing their physiology, partners helped stabilize each other’s responses and return more efficiently to equilibrium.

Moreover, I have demonstrated the implications of dyadic coregulation for individuals’ self-regulation (Zee & Bolger, in preparation-a). I found that physiological coregulation during discussions between partners predicted how individuals coped with a stressor: Among dyads who showed better coregulation, individuals later showed better self-regulation as they faced the stressor on their own.

This work emphasizes that physiological and emotional responses are shaped not only by individuals’ own self-regulatory efforts, but are also intricately tied to how they coordinate with others. This work underscores the importance of studying dyads as a unit and in doing so opens the door to identifying critical links between relationships and well-being. Collectively, these findings provide an exciting foundation for launching further lines of inquiry into coordination among partners and how such coordination impacts individual, interpersonal, and group success.

Statistical Methods

Statistical methods provide indispensable tools that allow me to address critical questions and achieve the most rigorous and theory-driven tests of my hypotheses. Across my lines of work, I implement and develop cutting-edge statistical methods focused on (1) modeling heterogeneity in psychological and interpersonal processes, (2) capturing dynamics of dyadic interaction, and (3) leveraging Bayesian estimation to better test theoretical predictions.

Modeling Between-Subject Heterogeneity

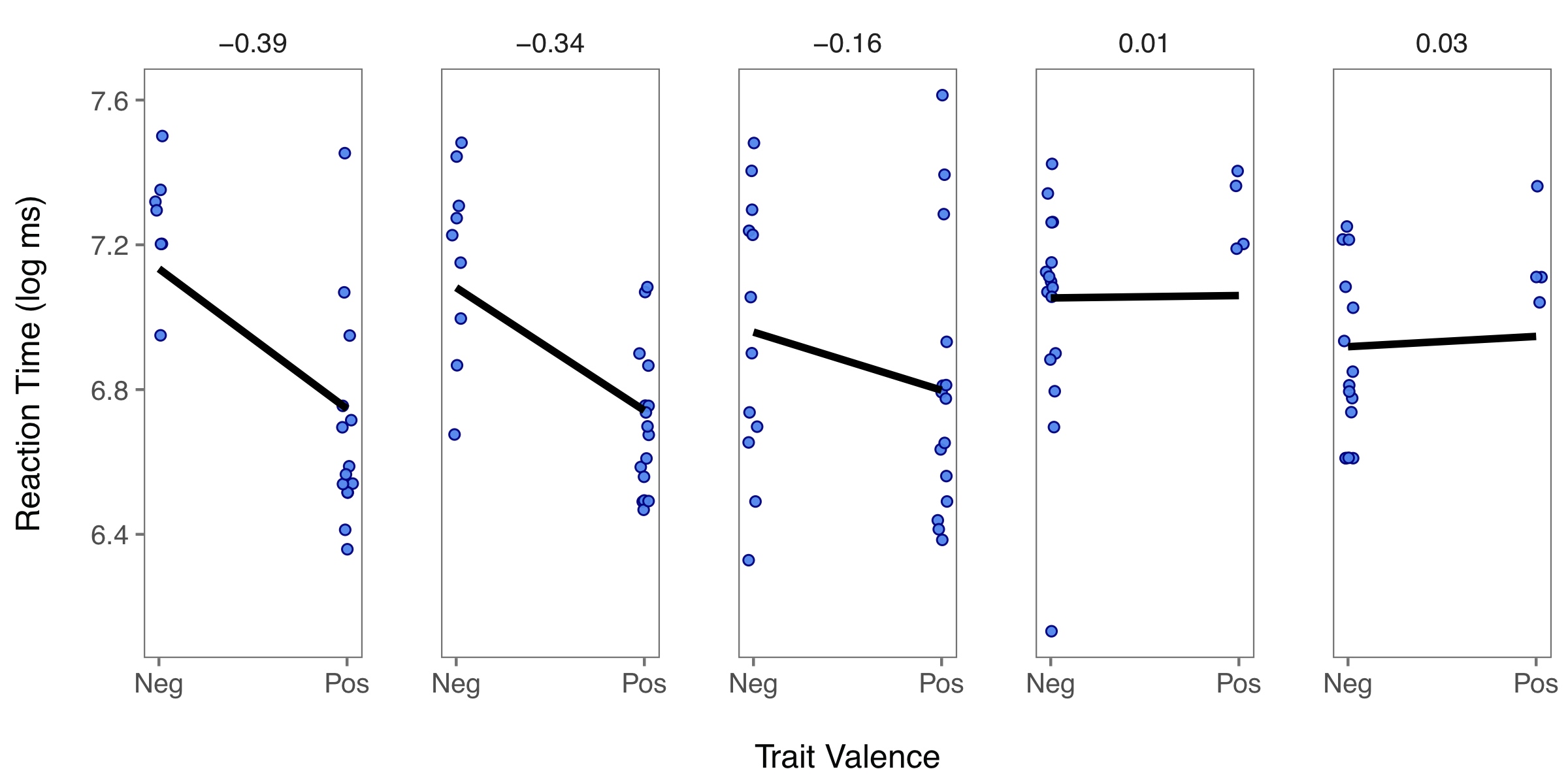

Not all people, studies, or variables are the same. Thus, I use multilevel modeling to assess heterogeneity in psychological processes. I have used this approach in a range of contexts, including cognitive experiments and dyadic interactions among both younger and older adults. In one project, my colleagues and I proposed the importance of working from the assumption that causal processes are heterogeneous (Bolger, Zee, Rossignac-Milon, & Hassin, 2019, Journal of Experimental Psychology: General). Across multiple studies in cognitive and social psychology, we used multilevel modeling to show that between-subject heterogeneity is often present, even in tightly controlled experiments. I have built on this approach in my other empirical work and emphasized the importance of heterogeneity for theory development (Bolger & Zee, 2019, Applied Psychology: Health and Wellbeing).

I have also used random effects to examine sources of heterogeneity beyond subject-level heterogeneity. For example, I have developed a way of summarizing complex results across outcomes and datasets by treating the outcomes and datasets as crossed random effects, while also assessing the degree of heterogeneity in both influences (Zee et al., 2020; Zee & Bolger, in preparation-b).

Panel plots showing between-subject heterogeneity in experimental effects for five subjects. Reproduced from Bolger, Zee, et al. (2019). Journal of Experimental Psychology: General.

Dynamic Modeling

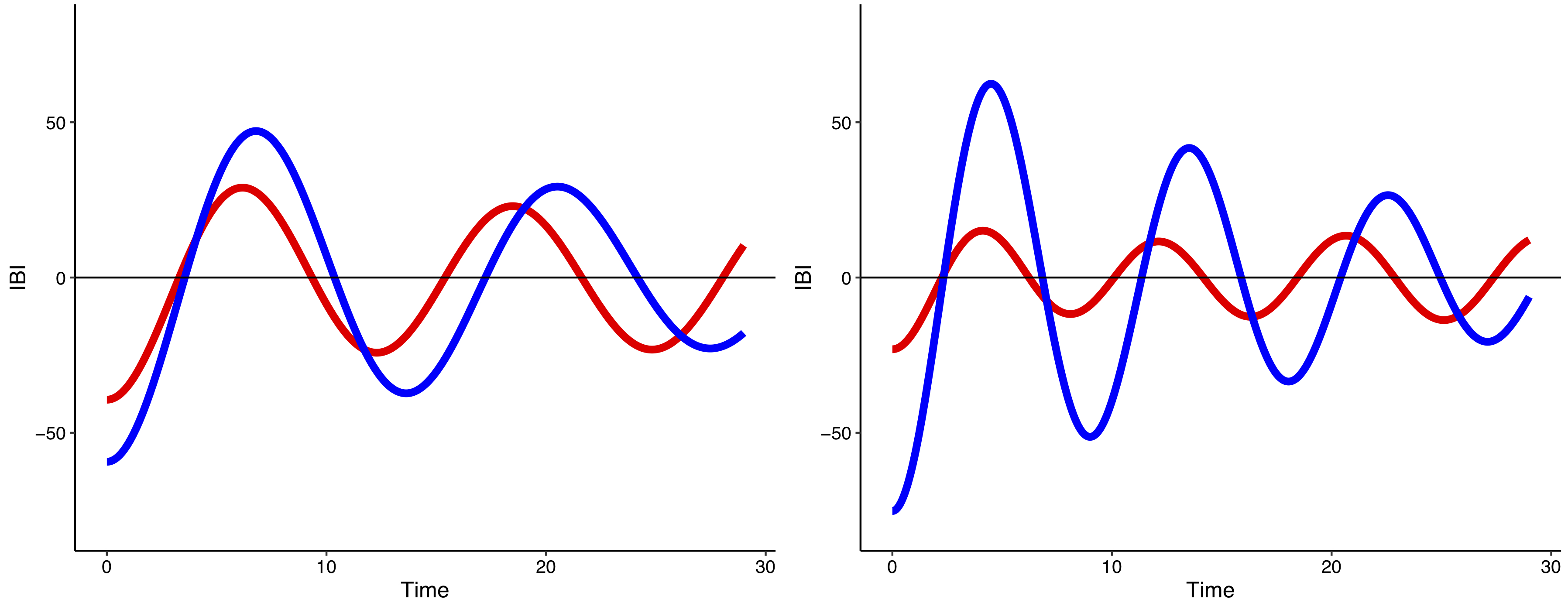

I combine dyadic analysis and time series analysis to model dynamics of interpersonal interactions. Much of my work in this area has focused on dynamical systems modeling. This method offers advantages over traditional linear approaches because they permit more targeted inferences about how people regulate their responses. These models can be fit so they produce coefficients that capture the rate of change (velocity) and speed of change (acceleration) in responses over time. I have used these models to reveal meaningful patterns of self- and coregulatory dynamics, such as how partners entrain each other’s physiological responses (Zee & Bolger, 2020, Multivariate Behavioral Research; Zee & Bolger, under review. Preprint).

Example results from dynamical systems analysis of dyadic physiological data.

Bayesian Estimation

Finally, I utilize Bayesian estimation to ask and answer new questions by drawing probability-based inferences about patterns of effects (Zee et al., 2020; Zee & Bolger, under review. Preprint). As one example, I have developed a way of synthesizing across model parameters using Bayesian posterior distributions. This method involves assessing whether the effect sizes of more than one predictor in a model all fall above or below a threshold value. This has proven especially useful in my work on coregulation. Because coregulation dynamics involve combinations of nonlinear effects, it can be difficult to gauge the nature of the coregulation process from individual coefficients alone. I have used my method, for instance, to calculate the probability of bidirectional coregulation effects occurring simultaneously (person A affecting person B, and person B affecting person A), an approach that would not be possible within the traditional frequentist framework.